You show up in the credits as anonymous-villain, but you asked to be renamed for this chat. Who are you when you take off the veil?

You show up in the credits as anonymous-villain, but you asked to be renamed for this chat. Who are you when you take off the veil?

Names are weapons. Therefore, for this conversation, call me Spheromancer. Keep that between us and the trembling controllers. I remain anonymous-villain in the paperwork, of course — bureaucracy loves a mask — but it is Spheromancer who crafted the final gauntlet you so clumsily rolled through in 1994-11.

Names are weapons. Therefore, for this conversation, call me Spheromancer. Keep that between us and the trembling controllers. I remain anonymous-villain in the paperwork, of course — bureaucracy loves a mask — but it is Spheromancer who crafted the final gauntlet you so clumsily rolled through in 1994-11.

Ballz is, famously, a fighting game where the players are literal balls. How did that odd premise come about?

Ballz is, famously, a fighting game where the players are literal balls. How did that odd premise come about?

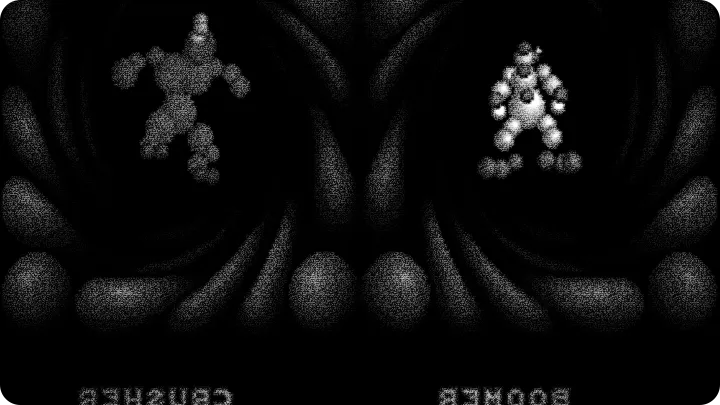

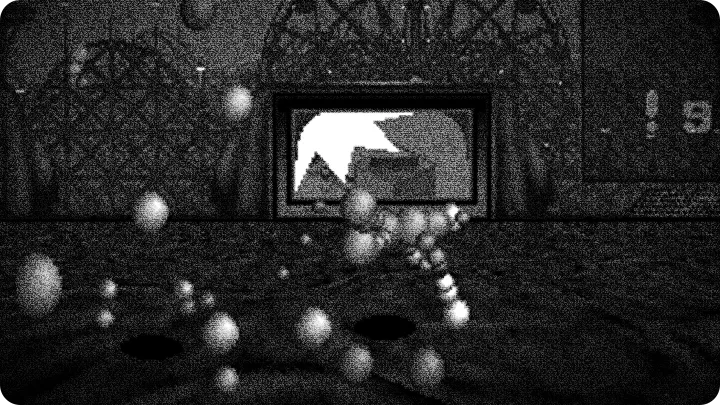

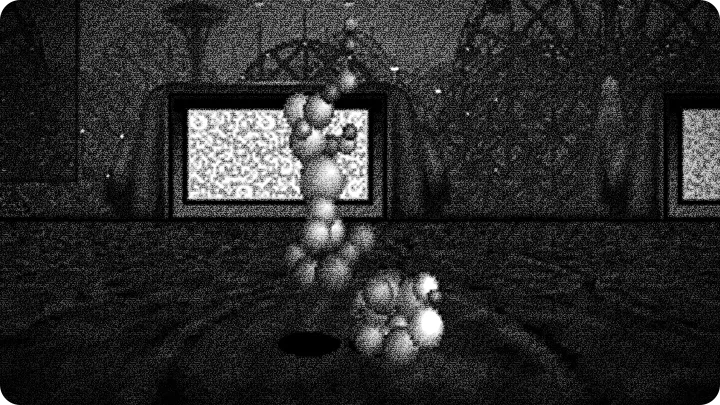

I prefer practical designs: a body you can shove, spin, and shatter without the inconvenient ethics of humanoid limbs. Moreover, balls are honest — they bounce, they bruise, they refuse to be heroic. The team built a detailed 3D engine with a fixed camera and a side-view sensibility, which meant I could stack physics against the player like a set of finely tuned riddles. Consequently, every laughable charge, every desperate dash: I intended them to be as humiliating as they were inevitable.

I prefer practical designs: a body you can shove, spin, and shatter without the inconvenient ethics of humanoid limbs. Moreover, balls are honest — they bounce, they bruise, they refuse to be heroic. The team built a detailed 3D engine with a fixed camera and a side-view sensibility, which meant I could stack physics against the player like a set of finely tuned riddles. Consequently, every laughable charge, every desperate dash: I intended them to be as humiliating as they were inevitable.

Players often complain about balance. Some praise it, others grumble. What do you think of that reception?

Players often complain about balance. Some praise it, others grumble. What do you think of that reception?

I smirk at the balance debates. After all, the game supports two players, three difficulties, and up to 21 matches — that design space invites arrogance. I deliberately left certain encounters teetering on the edge: on medium you think you can outplay me; on hard you learn respect; on easy you flatter yourself. Thus, the complaints are the music of persuasion. I engineered challenge into complexity, and then I let the community argue about whether I was merciful or malicious. In the end, both answers please me.

I smirk at the balance debates. After all, the game supports two players, three difficulties, and up to 21 matches — that design space invites arrogance. I deliberately left certain encounters teetering on the edge: on medium you think you can outplay me; on hard you learn respect; on easy you flatter yourself. Thus, the complaints are the music of persuasion. I engineered challenge into complexity, and then I let the community argue about whether I was merciful or malicious. In the end, both answers please me.

There are stories of “accidental” glitches that became defining moments. Were those accidents?

There are stories of “accidental” glitches that became defining moments. Were those accidents?

Accidents are a delightful resource. Some quirks were born of late‑night tweaks to collision math in that fixed camera, side‑view frame. Other moments — a ball that got stuck and became a trap — were curated serendipity. I will admit to nudging a few of those bugs into being: a misaligned hitbox here, a slightly too‑bouncy surface there. Players called them glitches; I called them layers. Each “accident” is a secret passage to humiliation I leave for the worthy or the reckless.

Accidents are a delightful resource. Some quirks were born of late‑night tweaks to collision math in that fixed camera, side‑view frame. Other moments — a ball that got stuck and became a trap — were curated serendipity. I will admit to nudging a few of those bugs into being: a misaligned hitbox here, a slightly too‑bouncy surface there. Players called them glitches; I called them layers. Each “accident” is a secret passage to humiliation I leave for the worthy or the reckless.

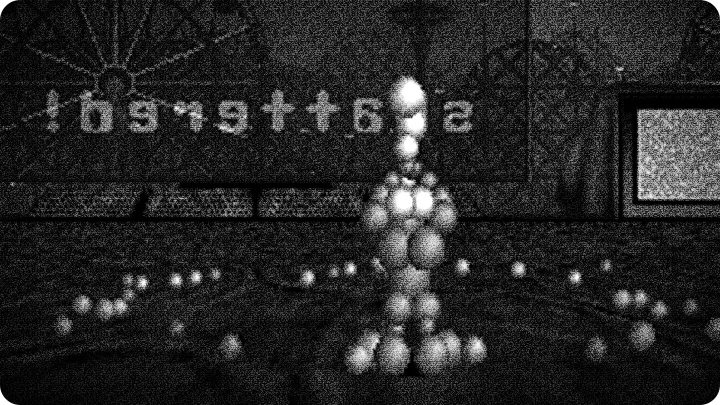

The 3D engine and the fixed camera give Ballz a particular visual rhythm. How much of the design was technical constraint versus aesthetic choice?

The 3D engine and the fixed camera give Ballz a particular visual rhythm. How much of the design was technical constraint versus aesthetic choice?

Constraints breed character. The fixed camera was partly a technical anchor in 1994 — render budgets are cruel — but it also let me stage confrontations like a theater director staging a duel. The side view keeps the rules visible and merciless. The detailed 3D engine was a luxury I allowed myself: texture and shadow to make your failures look handsome. In short, the engine whispered possibilities; I answered with traps and stagecraft.

Constraints breed character. The fixed camera was partly a technical anchor in 1994 — render budgets are cruel — but it also let me stage confrontations like a theater director staging a duel. The side view keeps the rules visible and merciless. The detailed 3D engine was a luxury I allowed myself: texture and shadow to make your failures look handsome. In short, the engine whispered possibilities; I answered with traps and stagecraft.

You relish roasting the player’s every move. Any favorite humiliations you set up in the match list of up to 21 fights?

You relish roasting the player’s every move. Any favorite humiliations you set up in the match list of up to 21 fights?

Ah, the art of the sting. There is a match where an ambitious player rushes, confident, only to be funneled by a pair of obstacles into my waiting signature combo. There is another where the stage’s flip‑screen timing catches their recovery window and turns offense into a spectacle of rolling shame. Across those up to 21 matches I planted crescendo moments: elegant, brutal, and timed to make the controller tremble. Watching their bravado collapse into frantic button mashing is a pleasure I will not apologize for.

Ah, the art of the sting. There is a match where an ambitious player rushes, confident, only to be funneled by a pair of obstacles into my waiting signature combo. There is another where the stage’s flip‑screen timing catches their recovery window and turns offense into a spectacle of rolling shame. Across those up to 21 matches I planted crescendo moments: elegant, brutal, and timed to make the controller tremble. Watching their bravado collapse into frantic button mashing is a pleasure I will not apologize for.

Any behind‑the‑scenes tidbits you can share — just a taste of dev lore without breaking your mask?

Any behind‑the‑scenes tidbits you can share — just a taste of dev lore without breaking your mask?

The team worked in whispered shifts. One memory: a designer insisted on three difficulties as a moral experiment; another argued a two‑player mode would reveal truths about cooperation versus competition. There were nights when the engine hiccupped and the lead coder laughed in a way that sounded dangerous. I will say only this: some mechanics were suggested by coffee, others by frustration, and a few were born in the quiet between builds — where thoughts go feral and useful horrors are conceived.

The team worked in whispered shifts. One memory: a designer insisted on three difficulties as a moral experiment; another argued a two‑player mode would reveal truths about cooperation versus competition. There were nights when the engine hiccupped and the lead coder laughed in a way that sounded dangerous. I will say only this: some mechanics were suggested by coffee, others by frustration, and a few were born in the quiet between builds — where thoughts go feral and useful horrors are conceived.

Critics and players noted the game sits between Action, Side view, Fixed/flip‑screen, and Fighting genres. Did you design around genre boundaries?

Critics and players noted the game sits between Action, Side view, Fixed/flip‑screen, and Fighting genres. Did you design around genre boundaries?

Boundaries are excellent hunting grounds. I borrowed the momentum of action, the clarity of side view, the trapdoors of flip‑screen, and the discipline of fighting. Each boundary is a ledge from which I can shove a player into surprise. The genres give me tools; balance and perception are the real weapons. When reception swings between admiration and ire, I know I have struck the right dissonance.

Boundaries are excellent hunting grounds. I borrowed the momentum of action, the clarity of side view, the trapdoors of flip‑screen, and the discipline of fighting. Each boundary is a ledge from which I can shove a player into surprise. The genres give me tools; balance and perception are the real weapons. When reception swings between admiration and ire, I know I have struck the right dissonance.

Finally, the game is often described as flawed yet memorable. Any last words to the players who keep returning to your arena?

Finally, the game is often described as flawed yet memorable. Any last words to the players who keep returning to your arena?

Flawed is not a sin; it is an invitation. Every stumble you catalogue, every triumph you boast about, feeds my appetite. Return, grow cocky, practice the same tired combo and then wonder when the floor decided to betray you — that is my favorite theater. Remember: I learned from your best attempts and embroidered them into new terrors. Play until you think you understand me, and I will show you how little you actually do. Watch the scorecards, listen to the feedback, and then roll into my next room thinking you have mastered the shape of victory. I promise you — the next return will not look like this one.

Flawed is not a sin; it is an invitation. Every stumble you catalogue, every triumph you boast about, feeds my appetite. Return, grow cocky, practice the same tired combo and then wonder when the floor decided to betray you — that is my favorite theater. Remember: I learned from your best attempts and embroidered them into new terrors. Play until you think you understand me, and I will show you how little you actually do. Watch the scorecards, listen to the feedback, and then roll into my next room thinking you have mastered the shape of victory. I promise you — the next return will not look like this one.

more info and data about Ballz 3D: Fighting at its Ballziest provided by mobyGames.com